Best Styles x Behavioural Finance

The illusion of knowledge and how to overcome the limits of learning

In the first article of our series “Best Styles X Behavioural Finance”, we looked at the two angels that guide our decision-making, the “rational angel” and the “instinctive angel”, how the latter may lead us to follow emotional or socially influenced trends, and how our Best Styles strategy harnesses our rational brain by remaining stoic and objective. Our instinctive angel may also twist what our rational angel tells us, however, and create the illusion of knowledge.

Learning is a human superpower. Over time, homo sapiens learned to master fire, developed language, created more and more elaborate tools – and transmitted all that knowledge to their descendants. Children learn the unique sounds and complex grammar of their mother tongue by simple exposure. And we never stop learning – pianists perfect their art over decades, scientists spend their lives probing the mysteries of quantum physics, football managers combine their on-the-pitch experience with the latest data models to constantly adapt their tactics.

Yet, there are limits to learning. In today’s complex world, no-one can become a specialist in everything. The days of the “Renaissance man” that was competent in the arts, the sciences, and politics to boot, are well over. That doesn’t prevent our instinctive angel from telling us that we can be such universalists. It succeeds in this by making us overconfident, by leading us to overestimate our abilities, or by ignoring data that doesn’t confirm our convictions – topics we’ll be exploring in this second paper.

How overconfidence broke the largest photography company

Before digital cameras and then smartphones became a thing, and making goofy photos of our pets became as easy and costless as the click of a button, photography was a comparatively expensive hobby that relied on analogue cameras and film.

Until the 1970s, one company was synonymous with photos: Eastman Kodak. Kodak’s dominant position in cameras, and especially in film, made it a hugely profitable company. So dominant, in fact, that when its engineers invented the digital camera in 1975, that innovation was put aside as it threatened the company’s cash cow: film. Kodak had stopped to learn. What followed were two decades of decline. The film business was upended by the emergence of Fujifilm, who entered the US market in the 1980s with lower-cost products. The death knell came in the 2000s when digital cameras (now produced by Kodak’s competitors) and then smartphones became the dominant photographic medium. The overconfidence of Kodak’s management in their business model clouded their perspective and led them to discard a promising innovation.

Investors, too, can be victims of overconfidence. Good stock picks will often be attributed to skill, even though other factors may be at play. During 2023-2024, for instance, the so-called Magnificent Seven stocks (Alphabet, Amazon, Apple, Meta, Microsoft, Nvidia and Tesla) dominated the US stock market and were its most prominent performance drivers. Picking the Magnificent Seven required little skill given the overall hype these stocks were subject to as AI emerged as a promising technology. But as the fortunes of these stocks began to diverge, overconfident investors may have missed the signs that should have prompted a reassessment of their positions. More generally, overconfident investors tend to take higher risks and forego diversification – a strategy that, over the long run, may result in larger losses than expected.

Why DIY is not the best approach to everything

This phenomenon is closely linked to another bias: overestimation of one’s abilities in an area where one is not an expert. Do-it-yourself (DIY) hardware stores are well aware of this bias and cater to it. In Germany alone, over 2000 hardware stores (more than in France and the UK combined, data from 2024) entice people to build their own gazebos, lay their own parquet floor or transform their balconies into an urban rainforest. Maybe not coincidentally, 12,000 Germans (mostly men) suffered DIY accidents that required treatment at a hospital (data from 2022).

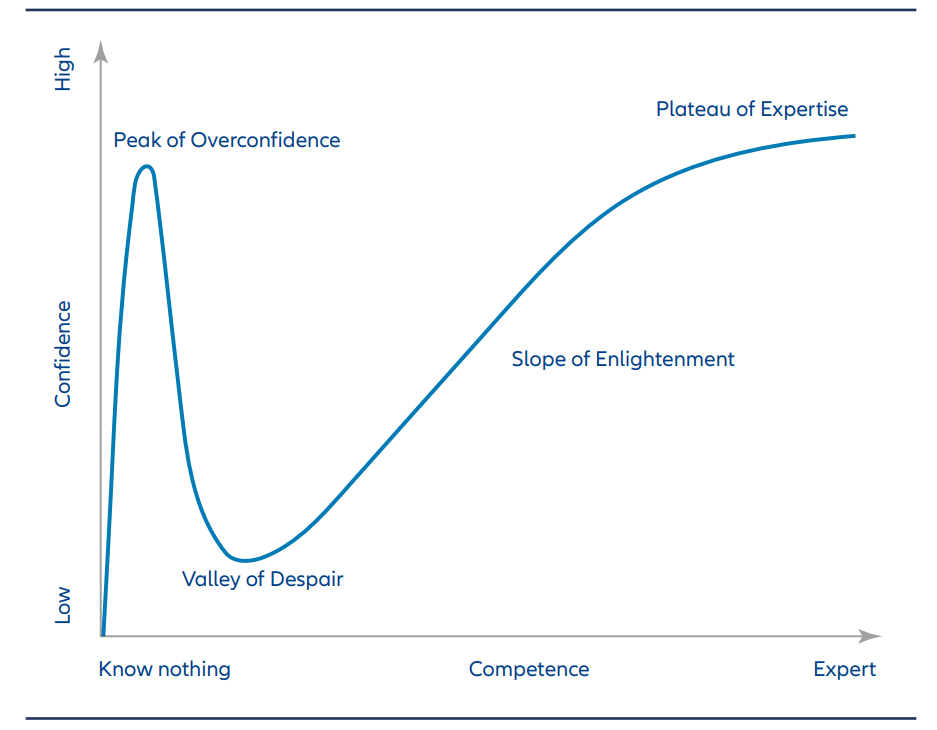

This phenomenon is encapsulated by the famous Dunning-Kruger effect: people that have just started learning a new skill – a language, a craft, investing – tend to vastly overestimate their capacities, leading to misunderstandings, accidents, losses. A euphoric peak is then followed by the realization that the subject is more complex than initially thought, before more learning and experience raise confidence to levels aligned with a person’s expertise.

Dunning-Kruger effect

Source: Allianz Global Investors. This is for illustrative purposes only

New investors can easily fall into this trap, especially when seeing early gains. Successes are then factors or to bad luck. Professional investors learn with time that humility is key, returns can’t be fully predicted and that the market has new lessons to teach every day.

Avoiding uncomfortable truths: Confirmation Bias

Humans like to believe they’re right. Our instinctive angel therefore has the tendency to encourage laziness in learning. Information that confirms what one already knows is often favoured compared to data that challenges it. Social media algorithms are built with exactly this confirmation bias in mind: more often than not, they will suggest videos and posts that align with content users previously consumed and liked.

For investors, confirmation bias can manifest in many ways. A person believing that a recession is imminent will favour economic data that confirms this belief, discard contrary information and invest accordingly. Conversely, an investor in an ailing company may focus too much on the encouraging words of its CEO and anecdotal evidence purporting to show that the situation is less dire than it actually is. Given the flood of information each of us nowadays has at their fingertips, confirmation bias is more rampant than ever: specifically sifting for the data that may contradict our beliefs is labour-intensive, time-consuming and unpleasant. Unfortunately, it is necessary if one wants to invest on the basis of the unvarnished truth.

How Best Styles deals with the limits of learning

Investors learn throughout their lives and careers, and many become very good at what they do. But they usually approach investing from one particular point of view, for example being a value investor or focusing on companies’ profitability. Becoming proficient at different ways of investing can be difficult.

Investors also tend to have something we call a “natural habitat”; an area of the market they go to or know well. This may be a region or a sector, larger companies or smaller companies. Many investors do not leave their comfort zone or, if they do, are not very successful. There is also a limit to how many companies an individual can research and analyse – and this makes a filter necessary. And even when such an enormous task is broken down by a larger team of analysts, there will be limitations to what they can cover in terms of breadth or depth.

Best Styles, on the other hand, integrates different investment styles within one approach, allowing us to test and probe the positive results of each of them, as well as for the combined strategy. The Best Styles approach can also be applied to a very broad investment universe of thousands of stocks globally (even though there might be some limitations regarding data availability).

Overconfidence is also an issue which, by design, is not generally associated with a systematic investment approach. Best Styles has been tried and tested over decades and the statistical methods employed to measure the success of our models is quite explicit when it comes to (statistical) confidence. It might actually be the other way around, that systematic investors are conscious of their potential shortcomings and try to mitigate them through diversification and risk management. And finally, a systematic approach cannot choose to ignore, consciously or unconsciously, the data available for processing. There is no opinion that needs to be confirmed, it is simply an objective process with biases limited as much as possible.

Overall, the Best Styles approach enables us to be knowledgeable about a lot of companies and apply different views, objectively and based on various investment styles. While more “rocket science” than “Renaissance man”, we believe that this can help investors reach their ultimate investment objectives.