Rising rates – a game changer for global financials

After a decade when money was cheap, or even free, high inflation now means interest rates have rapidly risen across the developed world. While most sectors will now face earnings headwinds from the higher cost of debt, financials are likely to be the primary beneficiary.

Key takeaways

- The large and rapid increase in interest rates since 2022 is a game changer for banks and insurers’ revenues and profits, which will take multiple years to fully play out

- We expect structural inflationary pressures to mean that rates will not soon revert to the very low levels seen for much of the past decade

- We continue to believe there are significant opportunities for investors to benefit from higher rates, particularly in Europe and Japan

A decade of interest rate headwinds

In the decade after the 2008 financial crisis, developed economies experienced a benign combination of moderate GDP (gross domestic product) growth and low inflation that allowed central banks to keep interest rates low. As financial markets acclimatised to this environment, yields on government and other bonds also declined. This low interest rate environment allowed borrowers to service existing debt while continuing to spend or invest. While most of the economy benefitted, this low interest rate environment was problematic for financial institutions: it is hard for them to operate when the price of their main product is zero or even negative.

Exhibit 1: Negative yielding debt peaked at $18trn in 2020

Amount of negative yielding debt (USD tn)

Source: Bloomberg, May 2023

Under normal circumstances, banks collect customers’ deposits and lend them out to other customers or invest them. Insurers similarly receive money from policyholders, which they invest to meet future claims. The interest income (or spread) they earn on these funds typically represents the majority of income for banks and life insurers. Low interest rates thus reduced these revenues.

These headwinds for financial firms from low interest rates was exacerbated by the Covid-19 pandemic. Faced with catastrophic damage to both human life and the economy, central banks in many developed economies responded by cutting rates and pumping liquidity into the system. Investors, faced with enormous uncertainty, rushed for the safety of bonds, even at low or negative yields. In late 2020, USD 18 trillion of publicly traded bonds had negative yields to maturity, according to Bloomberg estimates, representing more than a quarter of all investment grade debt (see Exhibit 1). Banks and insurers were thus faced with investing customer funds in a yield environment which guaranteed that, in many cases, they would get back less than they invested.

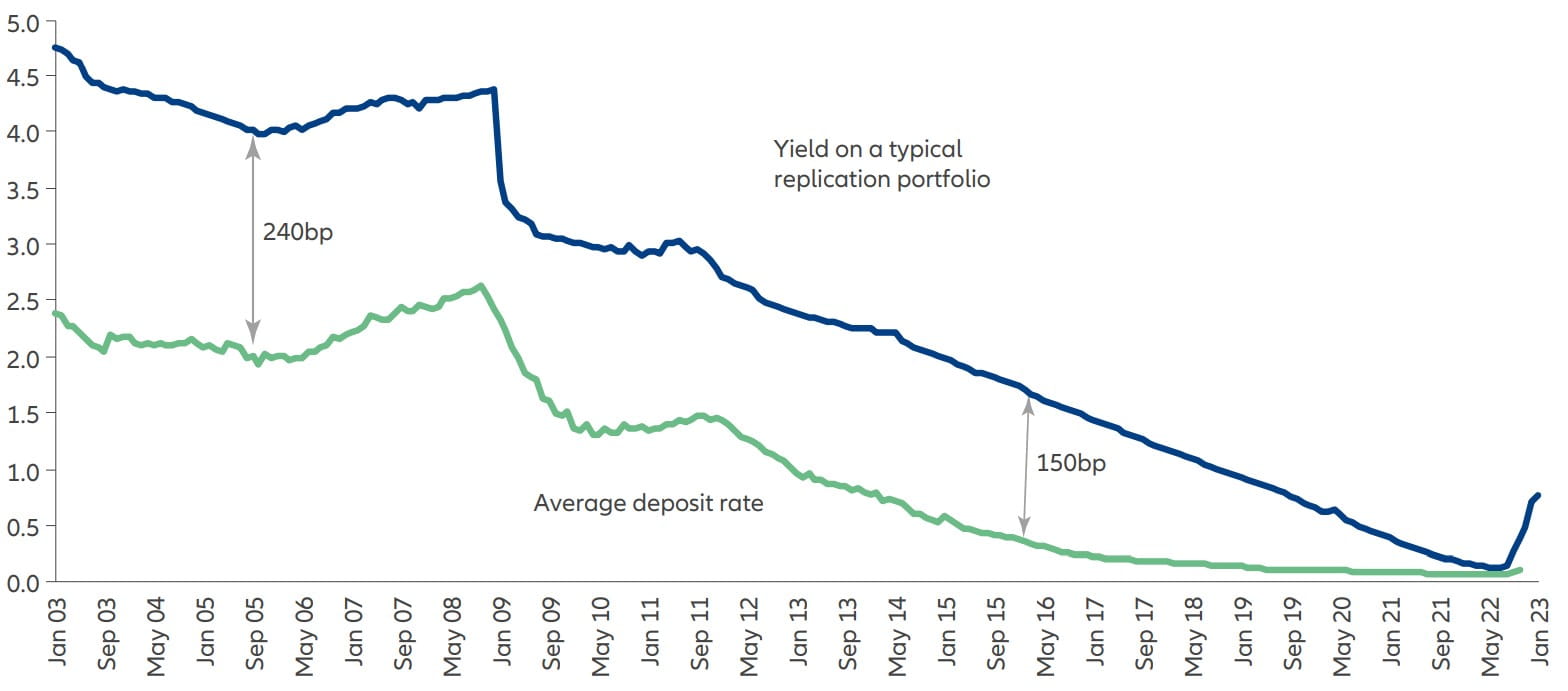

In a thought piece published in early 2022, we estimated that low interest rates in Europe were costing European banks EUR 100-150 billion in annual revenue relative to where rates had been in 2005: an amount comparable to their aggregate profit in 2022. Before the financial crisis, European banks would on average pay customers 2% interest for the money they borrowed and could invest the money in a portfolio yielding well over 4%, allowing the banks to earn a margin of around 240 basis points (or 2.4%). Lower interest rates and bond yields in the 2010s led to this margin declining to 150bp in 2015, and when rates turned negative for the Eurozone in 2016 this fell below 10bp in early 2022 (see Exhibit 2).

Exhibit 2: The yield spread on German bank deposits

Source: AllianzGI, May 2023

US financial firms were experiencing similar headwinds and responding by taking more risk on their investments. Despite this increase in riskiness, yields declined by around a quarter in the decade to 2021.

The rate environment inflection

As the worst of the pandemic passed and economies began to return to normal in late 2021, the inflation caused by the combination of continued supply chain disruptions and excess consumer savings has resulted in a significant shift in central bank policy. The Federal Reserve, European Central Bank (ECB) and the Bank of England raced to stop inflation expectations becoming embedded, raising rates by a greater amount and much faster than they had themselves expected only a few months earlier. The Federal Reserve raised rates by more than 4% in 9 months, the Bank of England by 3.5% in a year, while ECB raised rates by 2.5% in less than 6 months. Despite these rapid increases, inflation remains well above central bank targets in many developed countries. Investors expect more interest rate increases, and the yields on bonds have reacted accordingly: having peaked at USD 18 trillion in late 2020, the number of bonds outstanding with a negative yield hit zero in January 2023.

While these higher interest rates are adverse for consumers and borrowers, they represent a significant tailwind for banks and insurers. As the global economy begins to slow in the face of higher interest rates, higher inflation and higher energy costs, financials are seeing very large increases in income. Many US banks, who were well positioned for increases in interest rates, saw their Net Interest Income increase by more than 25% in the last three months of 2022 compared to the same period in the previous year. European banks are a little behind their US rivals as the ECB is later in the rate hike cycle, but we can already see deposit spreads widen from zero to over 90bp with a further sharp rise expected. We thus expect many firms in the financial sector to deliver strong revenue growth as they benefit from increases in interest rates, even as the wider economy slows.

What it means for investors: time torevisit financials

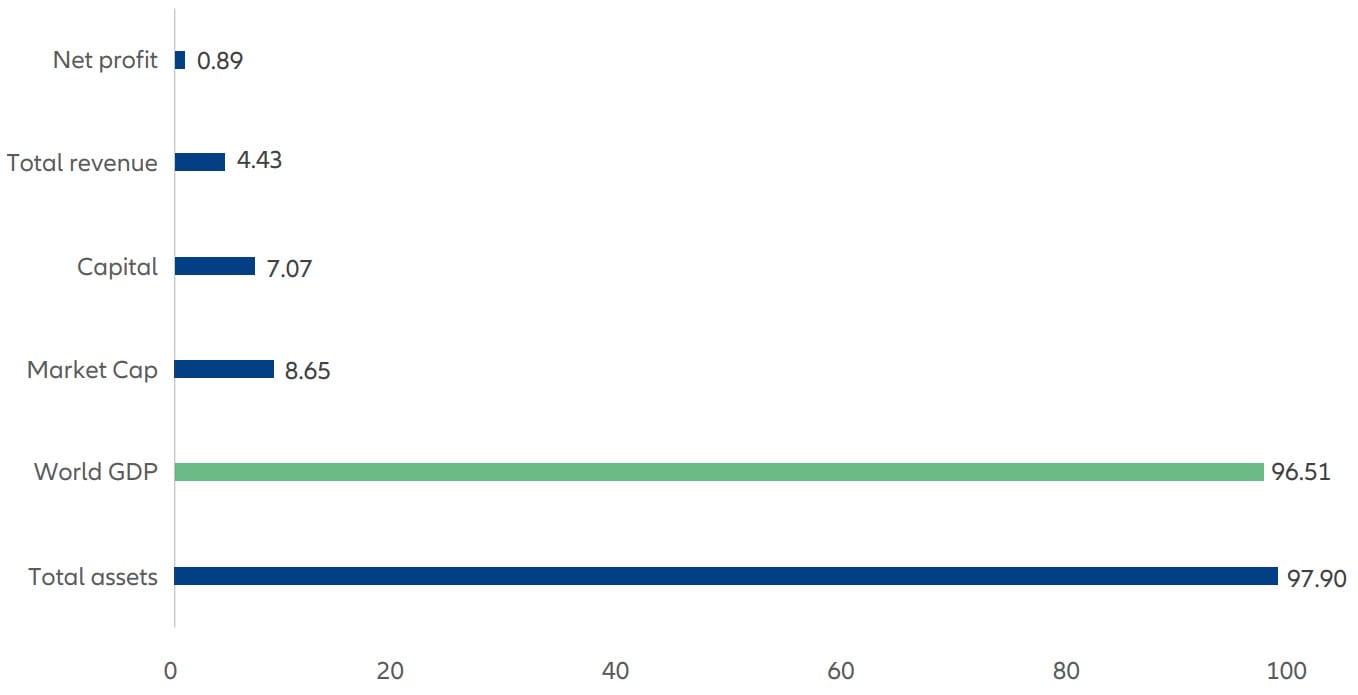

The financial industry is a large and critical part of the global economy, but often overlooked by investors as its performance was poor during the low rates phase. This should now change. The financial industry holds assets that exceed global GDP, and financial stocks represent nearly 15% of global equity market capitalisation. Against a backdrop of rising earnings and, in many cases, undemanding valuations (at least in Europe and Japan), investors would be wise not to ignore this sector.

Exhibit 3: Global financials have a large weight in the overall economy

MSCI Global Financials in Context (in USD tn)

Source: Bloomberg, May 2023

The sentiment on financials suffered a setback during the mini crisis for US regional banks and the Credit Suisse collapse. This shows that the higher rates also come with some risk for financials such as falling values of existing bond portfolios and maturity mismatch issues which need to be managed well. We believe that the crisis was due to some idiosyncratic management and regulatory failures. The affected banks have been taken over by competitors with no lasting problems for the wider system. Regulation for US regional banks will now be tightened while the European system proved resilient and will not be changed. This mini crisis has not changed our view on the opportunity for global financials in the face of higher rates.

Despite a much more supportive environment today than was the case in the period before the Covid-19 pandemic began, the financials are a smaller part of the global stock market today than they were in 2019, let alone before the financial crisis 2008. As profits from banks and insurers increase, we expect this to change.

Importantly, while some corporates have already begun to warn investors that their interest costs will rise due to higher interest rates, society more broadly will also have to come to terms with a world in which capital once again has a real cost. At the national level, governments will face significantly higher interest burdens on public debt balances which are elevated in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic. The increase in the cost of money also coincides with the beginning of a multi-decade green transition, with countries around the world needing to make vast investments in green infrastructure in order to meet their goals for Net Zero – i.e., balancing carbon emissions with the amount removed from the atmosphere. Society will need to find a way to still meet these demanding climate goals and make the necessary investments while managing the increased borrowing costs that higher interest rates entail.